Working with managers

Building a working relationship with your manager will help you grow your career, reduce stress, and even ship reliable software. Working with your manager requires mutual understanding. You must understand what your manager needs so you can help them. Likewise, your manager must understand your needs so they can help you.

Many kinds of managers

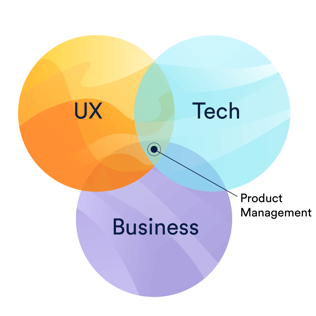

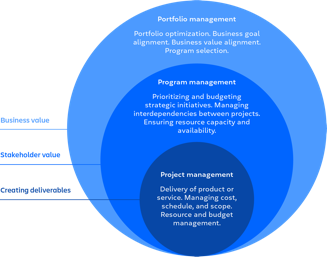

Product manager: A product manager’s role is strategic, much like a CEO but for the product.

His main responsibilities are:

Talking to users to gather requirements

Identifying problems and opportunities

Deciding which ones are worth going after

Creating a roadmap and defining features

Prioritizing development tickets

Project Manager: A project manager’s role, on the other hand, is more tactical, focusing primarily on the execution side.

His main responsibilities are:

Risk and issue management – involves spotting early on and minimizing potential risks that might delay the project completion.

Planning and resource scheduling – the planning part refers to adding up tasks with a start and end date, assigning the necessary employees to them, setting up the initial time budgets, and preparing the project timeline through specific project management methodologies and tools, like the Gantt Chart. The resource scheduling part, on the other hand, has to do with the daily management of task lists, materials, infrastructure, reports, and people to provide the project team with everything they need.

Scope management – perhaps the toughest activity of them all, it requires balancing the time-budget-quality trio to favorably modify the project scope and bring in line with the initial set outcome. For example, if you shortened the project timeline, then more resources are required which in return increases the budget. Or, you need to modify the scope to meet the quality agreed upon.

But in this section by Managers we will assume Engineering managers.

So what they Do:

Engineering managers work on people, product, and process.

Managers build teams, coach and grow engineers, and manage interpersonal dynamics.

Engineering managers also plan and coordinate product development.

They might also weigh in on technical aspects of product development—code reviews and architecture—but good engineering managers rarely write code.

Finally, managers iterate on team processes to keep them effective.

Managers “manage” all of this by working with higher-level executives or directors (“up”), with other managers (“sideways”), and with their team (“down”).

Managers manage down by tracking the progress of ongoing projects; setting expectations and giving feedback; providing visibility into relative priorities; hiring and, if necessary, firing; and maintaining team morale.

Communication, Goals, and Growth Processes

Managers create processes to keep teams and individuals running smoothly.

We covered the most common team-focused process framework, Agile

This section introduces you to processes you’ll use to maintain your relationship with your manager.

One-on-ones (1:1s) and progress-plans-problems (PPP) reports are used for communication and updates,

while objectives and key results (OKRs) and performance reviews manage goals and growth.

1:1s (One on ones):

One-on-ones are a dedicated time for you and your manager to discuss critical topics, address big-picture concerns, and build a productive long- term relationship.

You should set the agenda and do a lot of the talking in 1:1s. Prior to the meeting, share a bullet-point agenda with your manager.

Keep a 1:1 document that contains past agendas and notes.

We hit on two important points, so we’re going to stop and restate them: you set the agenda in a 1:1, and 1:1s are not for status updates.

Use the following prompts as topics for discussion:

BIG PICTURE What questions do you have about the company’s direction? What questions do you have about organizational changes?

FEEDBACK What could we be doing better? What do you think of the team’s planning process? What is your biggest technical concern? What do you wish you could do that you can’t? What is your biggest problem? What is the company’s biggest problem? What roadblocks are you or others on the team encounteing?

CAREER What career advice does your manager have for you? What can you improve on? What skills do you wish you had? What are your long-term goals, and how do you feel you’re tracking in them?

PERSONAL What’s new in your life? What personal issues should your manager be aware of?

You should have something to talk about most weeks.

If your manager repeatedly cancels your 1:1s, you need to speak to them about it.

Part of their job is to manage their team, and part of management is investing time with you.

Reach out to those who you think you could learn from.

PPPs (progress, plans, and problems):

A PPP is a commonly used status update format. A status update isn’t meant to account for your time; it’s meant to help your manager find problems, areas where you need context, and opportunities to connect you with the right people.

As the name implies, PPPs have a section for each of the P’s (progress, plans, and problems). Each section should have three to five bullet points in it, and each bullet point should be short, just one to three sentences. The whole process should take less than five minutes.

Share PPPs with your manager and anyone else who is interested—usually via email, Slack, or a wiki. Updates happen periodically, usually weekly or monthly, depending on the organization.

OKRs (Objectives and Key Results):

In the OKR framework, companies, teams, and individuals all define goals (objectives) and attach metrics (key results) to each objective.

Each objective has three to five key results, which are metrics that signal progress toward the objective.

Don’t make the key results a to-do list. They should spell out not how to do something but rather how you’ll know when something is done.

Objectives and key results are usually defined and evaluated quarterly. Work with your manager to understand company and team objectives. Use the higher-level objectives to define your OKRs. Try to have as few OKRs as possible; it’ll keep you focused.

Between one and three OKRs per quarter is a sweet spot. More than five and you’re spreading yourself too thin.

Most OKR implementations shoot for a 60 percent to 80 percent success rate, meaning 60 to 80 percent of the objectives are met.

If you’re hitting more than 80 percent of your objectives, you’re not being ambitious;

below 60 percent and you’re not being realistic or are failing to meet expectations.

Some companies use qualitative goals instead of OKRs. Others drop the “O” and focus only on the metrics—key performance indicators (KPIs)— without stating the objective explicitly.

Performance Reviews:

Managers conduct formal performance reviews at a regular cadence, usually annually or semiannually.

Title and compensation adjustments are generally made during review time, too.

Reviews are conducted using a tool or template with prompts like this:

What have you done this year?

What went well this year?

What could have gone better this year?

What do you want in your career?

Where do you see yourself in three to five years?

Employees self-evaluate first, and then managers respond. Finally, the manager and employee get together to discuss feedback. Employees normally need to sign off on the evaluation document after the discussion to acknowledge receiving it.

You should never be surprised by your performance review feedback; if you are, talk with your manager about the communication breakdown.

You might also be asked to participate in 360s (as in “360 degrees”), where employees solicit feedback from coworkers in all directions: above (managers), below (reports), and sideways (peers).

Managing Up

Get Feedback:

Reviews and 360s provide holistic feedback, but they are too infrequent to be relied upon solely. You need regular feedback so you can adjust quickly. Managers don’t always volunteer feedback, so you might have to ask. Use 1:1s to get feedback.

Ask for specific feedback

Don’t take feedback at face value. Your manager is just one perspective.

Give feedback on feedback too.

Give Feedback:

Managers need to know how things are going—what’s working and what’s not.

Every individual on the team is going to have a unique perspective.

Feedback eliminates blind spots.

Feedback can be about anything: the team, the company, behavior, projects, technical plans, or even human resource policies. Raise problems, but don’t focus solely on them. Positive feedback is just as valuable:

Use the Situation-Behavior-Impact (SBI) framework when providing feedback. First describe the situation. Then, describe the behavior: a specific behavior you find praiseworthy or problematic. Finally, explain the impact: the effect of the behavior and the reason it’s important.

The SBI framework avoids character judgments and assumptions about intention and motivation.

Note that you do not recommend a solution in the SBI framework. You might have solutions in mind, but it’s best to start with the issue and learn more before making recommendations. You might discover that you were mising valuable information or that a problem looks different than you thought.

Give feedback privately, calmly, and frequently. One-on-ones are an excellent venue. Feedback can trigger strong emotions but try to maintain a clear head and keep the conversation constructive.

Whether it’s feedback to your manager or your peers, and whether it’s written or verbal, always try to make it the kind of feedback you would want to receive.

Discuss Your Goals:

You need to clearly articulate your goals and aspirations for your manager to help you achieve them. Formal reviews are a great place for such conversations.

If you don’t have career goals yet, that’s fine. Tell your manager you want to explore; they’ll be able to help.

Take Action When Things Aren’t Working:

All we can say for certain is that you should be proactive if you feel things aren’t working.

Relationships and jobs have ups and downs. A short-term rough patch can happen and doesn’t need drastic action. If, however, you are feeling consistent frustration, stress, or unhappiness, you should speak up.

Use the SBI framework (from the “Give Feedback” section) to talk to your manager if you feel comfortable doing so.

Speak to human resources (HR), your manager’s manager, or other mentors if you aren’t comfortable speaking to your manager. The course you pursue depends on your relationship with each party. If you have nowhere to turn, use HR.

If you’re told things will change, give your manager time—three to six months is reasonable.

If time passes and you are still unhappy, it might be time for a transfer to another internal team or a new job.

Note

Sources:

The Missing README: A Guide for the New Software Engineer © 2021 by Chris Riccomini and Dmitriy Ryaboy, Chapter 13.

https://www.paymoapp.com/blog/product-manager-vs-project-manager/